The Most Mysterious Death Curse in Classical Music

If Beethoven turned emotion into math, then the next generation tried to turn math back into emotion—and it nearly destroyed them.

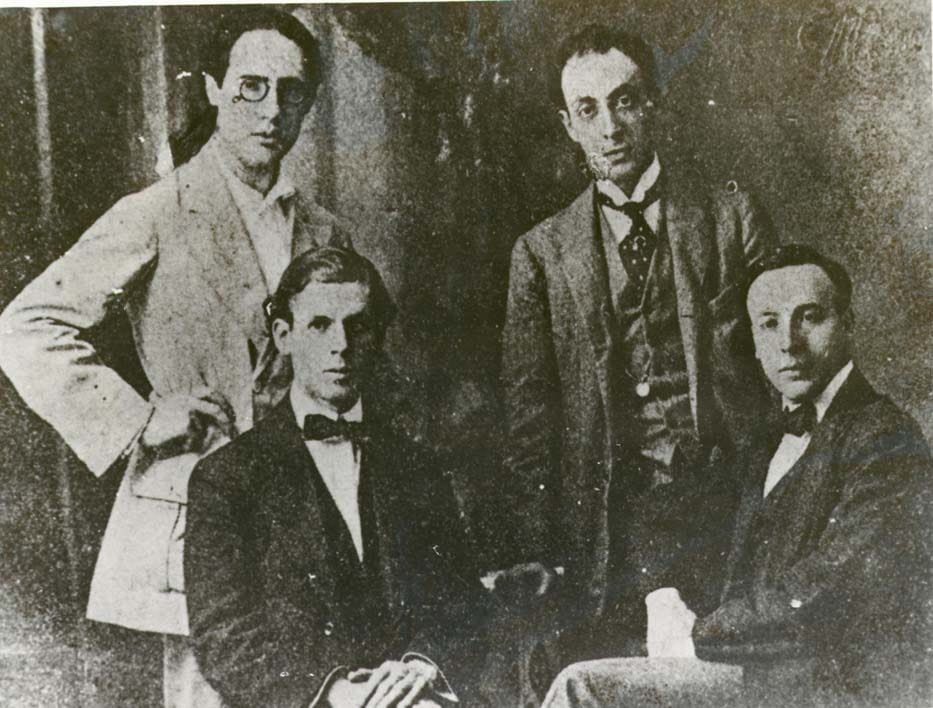

They were Arnold Schoenberg, Alban Berg, and Anton Webern, the so-called Second Viennese School.

They reinvented music in the early 1900s by throwing out melody, harmony, and key signatures altogether.

In their place, they built a new order based on twelve notes that refused to repeat.

It was radical, brilliant, and for the rest of the world… nearly unlistenable.

Breaking the Rules (and Themselves)

Schoenberg was the prophet. He believed that traditional tonality—the system that made Mozart and Beethoven sound logical—was finished.

He invented twelve-tone composition, where every note was used once before any could repeat.

To him, it was liberation. To audiences, it sounded like a panic attack.

His students, Berg and Webern, followed him into the wilderness.

Berg tried to blend structure with feeling, writing operas that sounded like nightmares wrapped in geometry.

Webern went further—stripping music down to whispers and silences so microscopic that his shortest pieces lasted under two minutes.

Together they were the first composers to treat sound like science.

And like many scientists, they were accused of playing God.

A School with a Body Count

The movement was cursed from the start.

Berg died suddenly in 1935 from an infected insect bite, leaving his masterpiece Lulu unfinished.

Webern accidentally shot himself dead in 1945 when an American soldier mistook his pipe light for gunfire.

Schoenberg, the only one who lived long enough to see fame, spent his later years in exile in Los Angeles—paranoid, broke, and terrified of the number 13. (He died on Friday the 13th.)

Three men, three obsessions, three deaths that felt poetic in all the wrong ways.

They didn’t just break music’s rules—they broke themselves trying to rebuild it.

When Genius Outruns the Audience

Atonality wasn’t designed for applause. It was designed for truth—an attempt to express the modern world’s anxiety with mathematical honesty.

World wars, fascism, and industrial noise had shattered the old order. The idea of “pretty” music felt fake.

Schoenberg’s disciples wrote for a century that no longer believed in harmony.

But culture moves in loops. What was once heresy became foundation.

Today, film composers, jazz theorists, and ambient producers all borrow from the chaos Schoenberg unleashed.

You’ve heard his ghost every time a movie score builds dread without melody.

The Real Curse

The “curse” wasn’t supernatural—it was historical.

They lived at a moment when art stopped comforting and started diagnosing.

They didn’t write to be loved; they wrote to be honest, and honesty isn’t always profitable.

Their music sounded like the 20th century before the 20th century knew what it was.

They were simply too early.

Editorial Note:

This article was drafted with assistance from AI (text generation and outlining). All facts, structure, and final wording were reviewed and approved by the author. Learn more.