59 Signatures and a Severed Head: The Most Macabre Document in History

On a freezing January morning in 1649, a group of English revolutionaries gathered around a single piece of parchment that would change the course of history. The paper was short, precise, and murderous — an order for the execution of King Charles I.

It wasn’t just the fall of a man; it was the death of the divine right of kings. This was bureaucracy turned lethal — a document so cold and final that it still hums with treason.

When Power and Faith Collided

Charles I spent two decades ruling like God’s personal intern — dissolving parliaments, raising taxes, and forcing the country toward civil war. England had had enough.

By 1648, the king had lost the war, been imprisoned, and still refused to accept that Parliament had any authority over him. To the army and its leaders, he wasn’t a ruler anymore — he was a repeat offender. So they did the unthinkable: created a court to try their own monarch.

The Trial That Shouldn’t Have Happened

The trial of Charles I was an improvised legal stunt. He refused to plead, insisting that no earthly power could judge him. Parliament begged to differ.

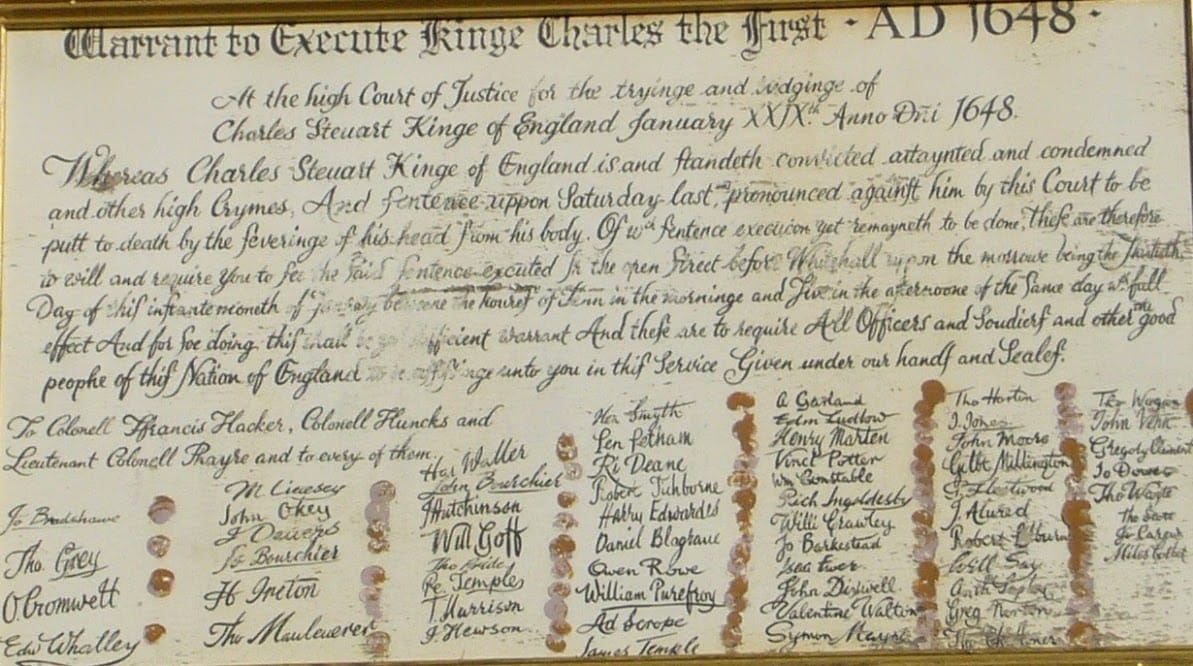

The charge was simple: treason against his own people. After days of theatre and defiance, fifty-nine commissioners signed a document ordering his execution. They knew it was a death sentence for a king — and possibly for themselves.

The Hardest Paper Ever Written

The death warrant of Charles I isn’t poetic. It reads like a memo from hell: the king “shall be put to death by the severing of his head from his body.”

No metaphors. No prayers. Just an execution schedule for a monarch. Each signature on that parchment is a small act of rebellion against a thousand years of divine order. Every wax seal is a political time bomb. They weren’t just killing a king — they were signing off on the idea that kings could be killed.

One Stroke to End an Empire

On January 30, 1649, Charles I walked onto a scaffold outside the Banqueting House in Whitehall. He wore two shirts so the cold wouldn’t make him tremble. He spoke calmly to the crowd, then laid his head on the block.

One clean swing from the executioner’s axe, and the crowd groaned as a nation’s identity split from its body. England was no longer a kingdom; it was an experiment. For the next decade, the country became a republic under Oliver Cromwell — a regime built on that very piece of paper.

Regicide Comes With Receipts

When the monarchy returned in 1660, the men who signed the warrant paid the price. Some were executed. Others were exhumed and publicly hanged for show. A few escaped to Europe or the New World, haunted by their signatures.

The death warrant itself was kept as evidence — a receipt for regicide. It’s still there today in the British Parliamentary Archives, its edges browned and seals crumbling, yet it still feels dangerous to look at.

Why It Still Slaps

The document that killed Charles I did more than end a king — it invented modern accountability. It proved that no one, not even the divine, is above a signature.

Every modern constitution, every vote, every law that checks power traces its shadow to this moment when ink beat blood. The Death Warrant of Charles I is still the hardest document in history because it didn’t just take a life — it ended an entire cosmic idea.

This article was drafted with assistance from AI (text generation and outlining). All facts, structure, and final wording were reviewed and approved by the author.